JAREMIANKA

Maria Jarema at the ball, Cracow, 1930s, Family archive, courtesy of Aleksander Filipowicz

SLEEPY PUPPETS IN COLORFUL BODYSTOCKINS: COSTUMES BY JAREMINKA

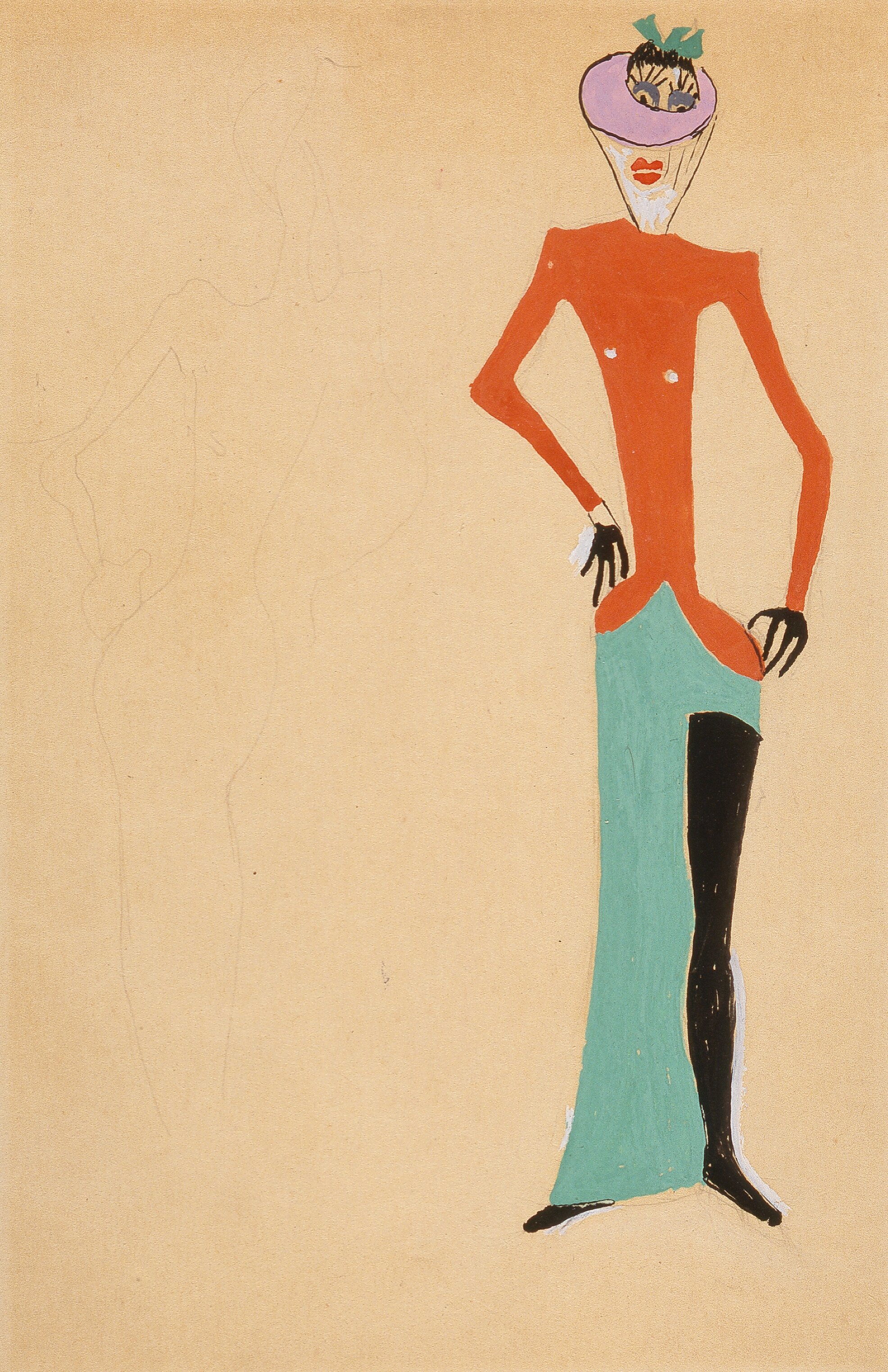

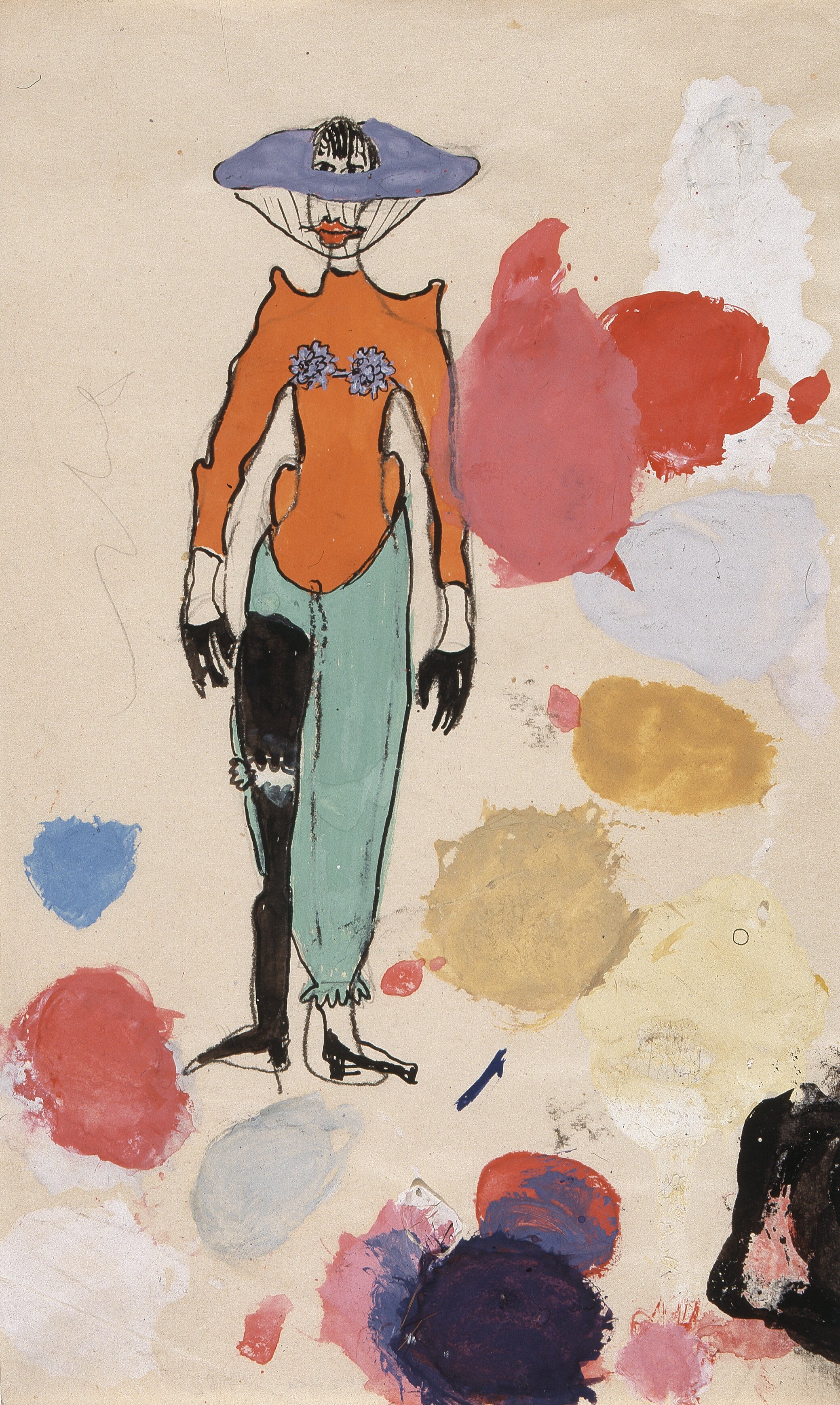

Maria Jarema, Costume Designs for the Unidentified Cricot Theater Performance, 1930s, From the Deposit of the National Museum in Wrocław, courtesy of Aleksander Filipowicz

Straight, dark hair cut just under the chin line, a semicircular fringe, and a characteristic hat. A red beret with an antenna or fabrics decorated with stars. In a skirt, or more often trousers, with a worker’s bag hanging from her shoulder. In Kraków in the 1930s Maria Jarema stirred a sensation just from her look. She passed for a beautiful revolutionary, but also a feminist, known for her acerbic wit and sharp tongue.

Near the end of her life, in the 1950s, she always dressed in black, with a newsboy cap and a short, boyish haircut. And a bit like a young boy, she was also said to behave roguishly. She drank black coffee, smoked cigarettes, and didn’t beat around the bush.

Maria Jarema, Costume design for an unidentified Cricot theater performance, 1930s, From the deposit of the National Museum in Wrocław, courtesy of Aleksander Filipowicz

With her dress and hairstyle she stuck out among her colleagues. She came across as a Modern Woman, whom, playing more herself than anyone else, she embodied in a performance. One of her colleagues from the Kraków Group, Jonasz Stern, recalled that because of the way she dressed, people shouted at her in the street, and Juliusz Kydryński prefaced an interview with the artist in Przekrój with an extensive description of her sheepskin coat, sewn together of patches big and small. In Paris she not only toured avant-garde art, but also the Parisian streets and shop displays. In their letters, she and her female artist friends exchanged observations on fashion. Erna Rosenstein wrote of fashionable crimson and Hanka Rudzka-Cybisowa of dry stalks among lace and brocade. After returning to Paris with a scholarship, she sewed from scarves an immodestly tight ball gown. In black, of course. But at the café balls popular at the time she could as easily be seen in a tuxedo, her hair slicked down with pomade. From her last trip to Paris she brought back stylish suede pumps.

Maria Jarema, 1940s, Family Archives, courtesy of Aleksander Filipowicz

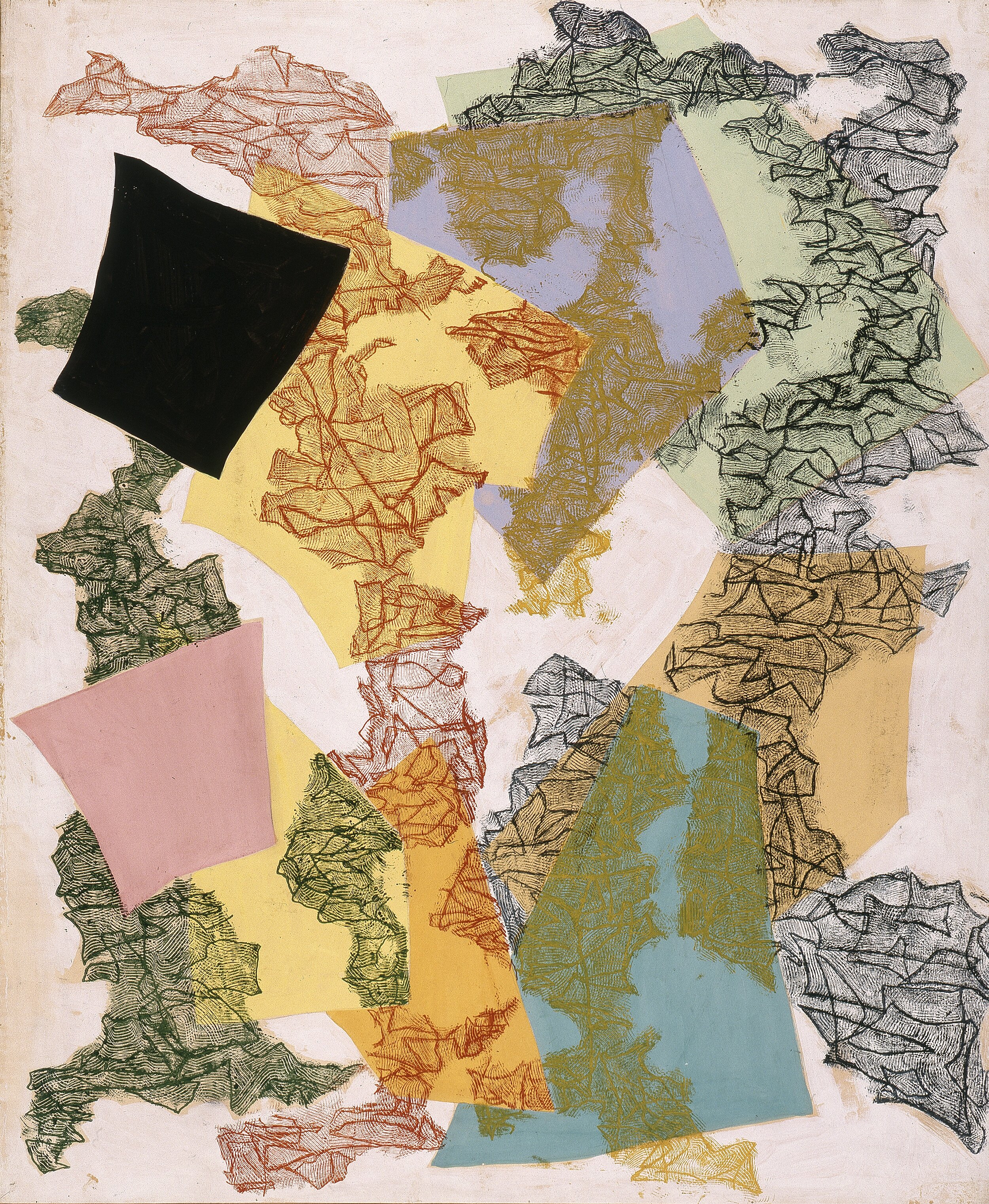

Although she studied sculpture at the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts, and is best known for her later geometrical and kinetic abstractions—works on paper, where she combined monotyping with tempera—nowadays it is the costumes she designed that primarily attract attention. Forgotten quasi-sculptures that the artist executed for the pre-war Cricot theatre of visual artists and the Cricot 2 reactivated after the war. They were actually small theatres sharing space with a café—experimental, independent stages instigated, as the press put it, by painters and brawlers. Jarema worked on a dozen or more shows and executed dozens of costumes. Our knowledge of the costumes is only fragmentary, gleaned from rough drawings in sketchbooks, mentions in theatre reviews, and a dozen or so black-and-white photos.

Ironically, while nearly her entire wardrobe, drenched in the scent of mothballs mingled with a fug of French perfume, remained folded up in the attic of her family home, just a few of her costumes survived. All of them from the post-war years. And even that is probably only because the director of Galeria Krzysztofory, where the Cricot 2 found its permanent base, decided to stuff them into a crumbling chimney.

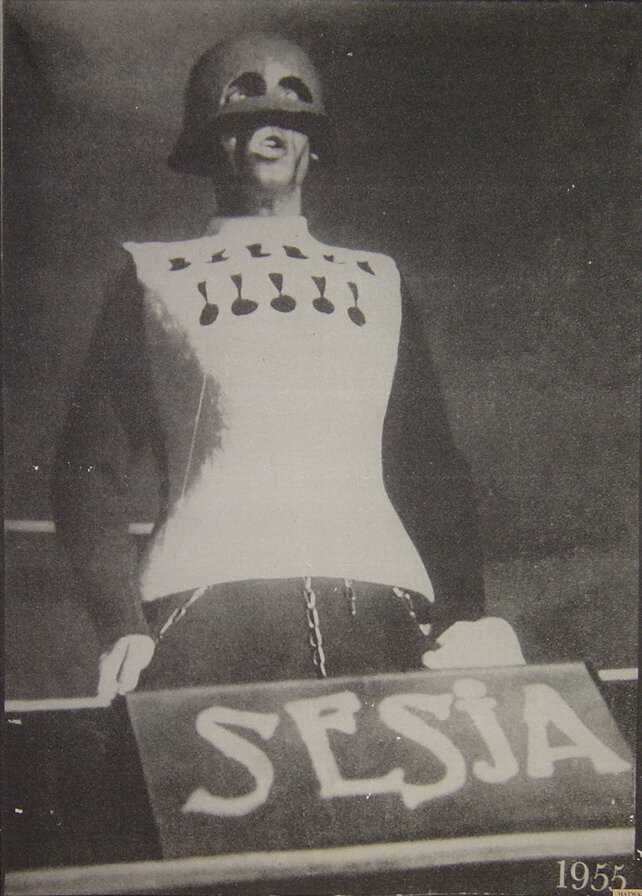

Jerzy Nowak as Hyrkan IV. Scene from the play "Mątwa" by S. I. Witkiewicz, 1956, photo unknown

Maria Jarema as Matrona (in the background the Statue of Alice d’Or). Scene from the play "Mątwa" by S. I. Witkiewicz, 1956, photo unknown

After a decade or so the costumes were rescued by Tadeusz Kantor, the Cricot 2 director, with whom Jarema would conduct endless discussions during rehearsals, often ending in spectacular quarrels. But Kantor “improved” the costumes by stuffing them with fragments of mannequins. Kantor wrote of the costumes designed by Jarema that they were autonomous forms, like the actor’s second skin, reinforcing his expression but also extending beyond the rigid construction of the body. Kantor saw in them the embodiment of the dream of modern theatre, where the boundaries between fiction and reality are blurred, and the costume does not dress the character but becomes an extension of the character—like the character’s double.

Maria Jarema, Design of the costume of the figure of Pope Julius II to "Mątwa" by S. I. Witkiewicz, 1956, tempera and crayon on paper, from the deposit of the National Museum in Wrocław, courtesy of Aleksander Filipowicz

Cricot 2 was established by Jarema, Kantor and Kazimierz Mikulski in 1955. They had thought of it earlier, but socialism, which initially they believed in, not only quickly disappointed them and but also betrayed them, socially and artistically, by introducing the doctrine of social realism: propaganda art, produced on an assembly line and practically under compulsion—art for the masses. They performed Witkacy’s Cuttlefish, referencing the pre-war staging and also, allusively, the current political situation, so far as they managed to throw dust in the censor’s eyes. The Cuttlefish, or the Hyrcanian World View, full of juicy characters—frustrated artists, women unhappy in love, and insane hypocrites—dealing with the world of the sleepy Hyrcania, the decline of religion, philosophy and art, became in the context of the post-Stalinist thaw a symptomatic orgy of power.

Maria Jarema, Design of the costume of Matrona's character for "Mątwy" by S. I. Witkiewicz, 1956, tempera on paper, from the deposit of the National Museum in Wrocław, courtesy of Aleksander Filipowicz

Jarema toyed with Witkacy. She created costumes primarily based on bodystockings (trykoty), which quickly translated into a hilarious nickname for the Cricot: Tricot. The costumes drew from the text all of the deformity and grotesque, further amplifying it, and imposed on the actors fundamental gestures. The stage was populated with marionettes struggling with existential guts, moving in a somnambulant trance. Among them was Pope Julius II in his distinctive tiara of cone-shaped felt, wrapped in black coils of tape, with a red glove, suggestive of a ritual mummy but also a liturgical jester. Ella, in a short blouse with a drawing of an upside-down, geometrical face, as the embodiment of innocence exclaimed onstage: “I am not as innocent as you think. I also have some venom in me!” And her reflection in a crooked mirror: the statue of Alice d’Or posed as an enigmatic and eroticized sphinx. An objectified woman, a vamp in a tight red jumpsuit with bared breasts, around which the Dead Wives circulated like moths fluttering shreds of veils. Jarema dressed them, as she also did the lackey Tetricon, in asymmetrical bodysuits. Black and white, strongly cubist, supplemented by overdrawn makeup, full of black patches. Two uncles appeared as Siamese twins, grown together under the same jacket, Bezdeka, the protagonist classically in black, and Hycan in a mask/helmet, replete with military accessories and the geometrical ornament of medals on his chest. The icing on the cake was the character of the Matron, or more accurately Matrons, to whom Jarema devoted the most space in her sketchbook. Perhaps for good reason, as she herself played one of them. Dressed similarly, one in orange with an embroidered veil, the other in violet with an asymmetrical skirt exposing her legs, both in masks of lips crowned by a frivolous bow, led an ambivalent game with the figure of the matron/harlot. They uttered lines, but their lips remained immobile.

Maria Jarema, Design of the costume of Matrona's character for "Mątwy" by S. I. Witkiewicz, 1956, tempera on paper, from the deposit of the National Museum in Wrocław, courtesy of Aleksander Filipowicz

“From Kantor’s Cuttlefish I remember only the costumes and the masks,” Elżbieta Wysińska wrote years later. “Garish blotches of clothing and glaring blotches on the faces.” She referred to Kantor and Jaremianka’s staging as the burial of realism.

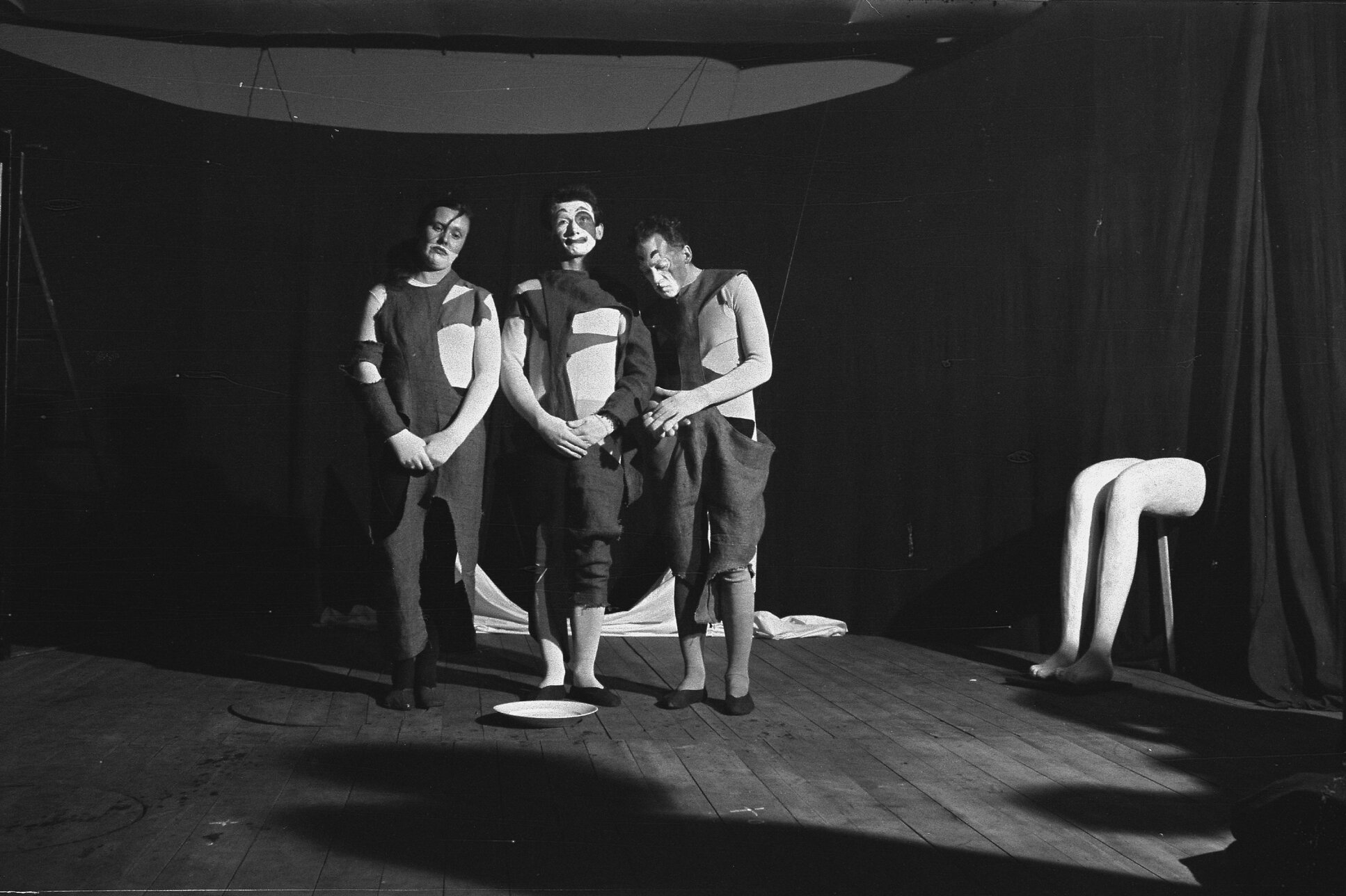

Although the plot of The Cuttlefish, revolving around destruction and nonsense, seemed to proliferate metaphysical senses and moral dilemmas, the next show by the Cricot team was based on a simple story: the wife of a circus manager falls in love with an unemployed clown and decides to rid herself of her inconvenient husband. Circus, by Mikulski, a painter and one of the founders of Cricot 2, surrealist in expression, required not so much the grotesque as a spirit of abstraction. Jaremianka decided on a stage design limited to the minimum and deconstructivist costumes revealing the structure of the body. Or, to put it differently, as the critics wrote, aestheticized tatters full of strange holes. The raw linen was supplemented by geometrical patches of pure colours, revealing a kinship with the artist’s painting, and the entire costume maintained the aesthetic of commedia dell’arte, adorned with tawdry poetics. The costumes were complemented by painted masks, like the costume of dancer Maria Mikuszewska in the first Cricot, directly on the actors’ bodies, and characteristic black umbrellas full of holes. In making up the faces, Jarema sometimes used such elements as a wisp of hair or a mole. A departure from the specific circus quality, lined with misery, was the shirt of one of the protagonists stuffed with newspapers, and the extremely low-cut costumes of the vaulters, sewn from black oilcloth.

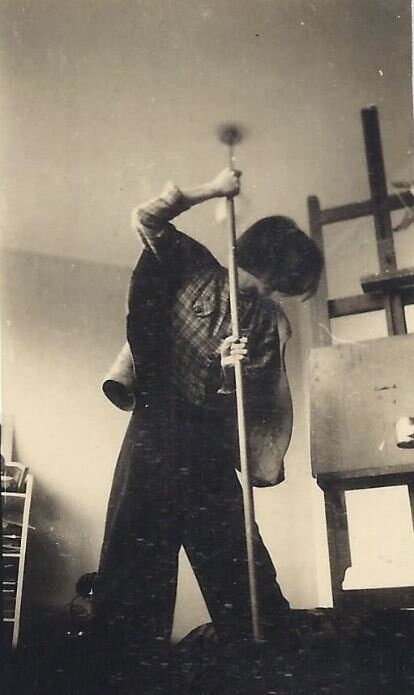

Maria Jarema in the studio, Cracow, 1940s, Family archive, courtesy of Aleksander Filipowicz

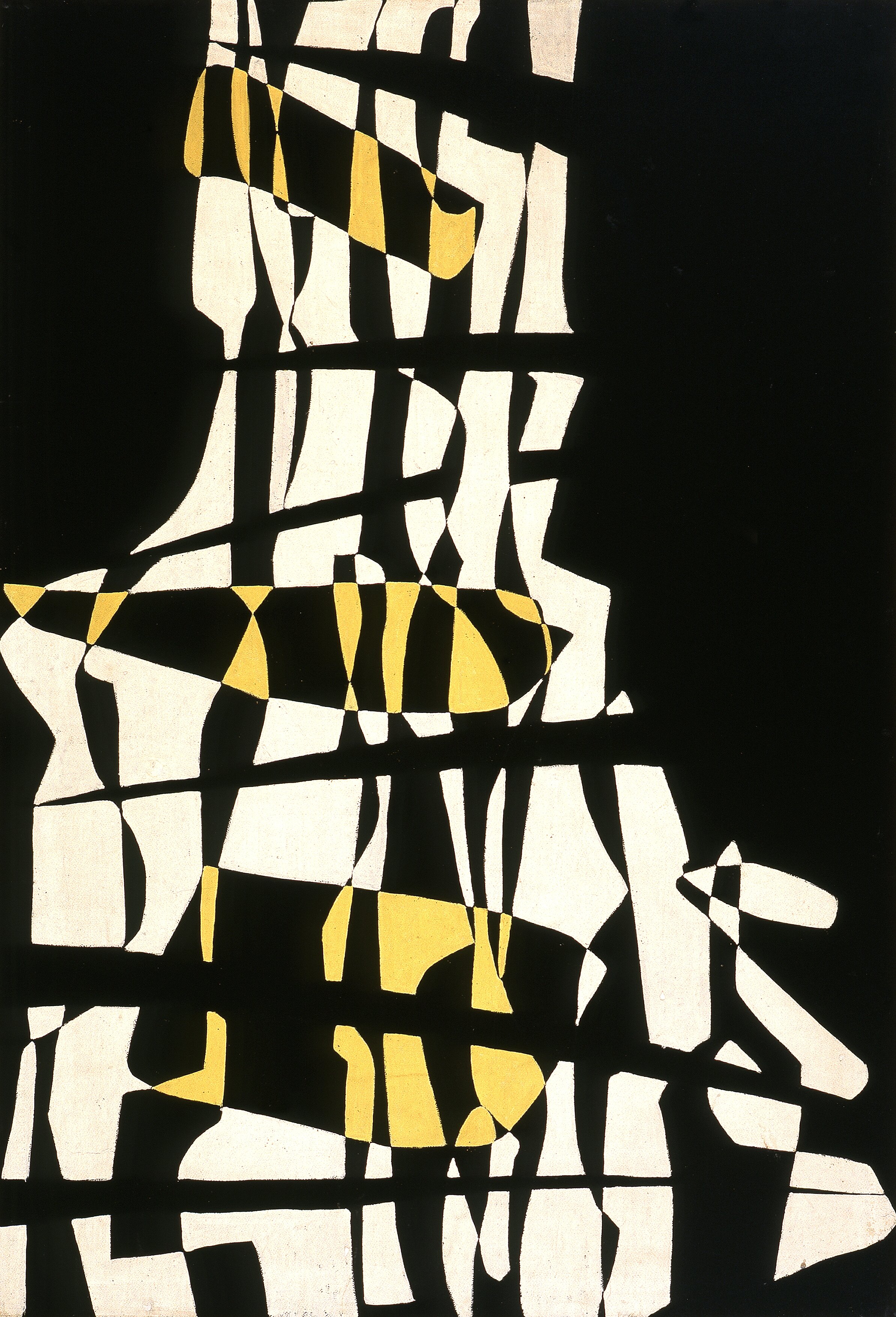

Maria Jarema, Rhythm I, tempera on paper, from the deposit of the National Museum in Wrocław, courtesy of Aleksander Filipowicz

The costumes for the Cricot 2 theatre accentuated contrasts, the process of breaking down the human figure, dismantling and dismembering structures. Behind the Iron Curtain they constituted a breath of the avant-garde, the first of their kind, and the first fresh breeze after years of Stalinist terror. We don’t know whether Jarema sewed them herself or only assisted. In one of her notebooks, under the heading Cuttlefish, she wrote of the need to borrow a sewing machine, and she supplemented some of the designs with swatches of materials. There are six costumes that have survived to this day, partially broken up and partially reconstructed. We know very little of her other projects, and sometimes little more than the fact that they did take place.

Maria Jarema, Filtry, 1958, monotype and tempera on paper, from the deposit of the National Museum in Wrocław, courtesy of Aleksander Filipowicz

Scene from K. Mikulski's Circus, 1957, photo: Aleksander Wasilewicz, courtesy of Tomisław Wasilewicz

Characterization of the character for the play "Circus" by K. Mikulski, 1957, photo: Aleksander Wasilewicz, courtesy of Tomisław Wasilewicz

Maria Jarema died of leukaemia, a year after the premiere of Circus. When she was ill, she reportedly worked even more hungrily and insatiably. She was treated among places at a clinic in Paris. There she met the poet and writer Tadeusz Różewicz, who portrayed her in his story “In the Most Beautiful City in the World” as M., a painter who was very sick but haughty and spiteful. He wrote that her paintings fed on their own creator, leaving behind a puppet in a topcoat and stuffed trousers—a puppet that shrugs and says it won’t paint the bard’s trousers, even very beautiful trousers.

Although Jarema would probably have nothing against “remaining in that theatre,” as announced in her day by the character of the Modern Woman which she played, this stage can be seen as yet another masquerade, a bohemian game of dress-up, or a kind of ironic repetition leading unconsciously to a place on another stage. But also an act of subversion allowing her to exist outside the field of vision, in this and other puppets, in costumes, sculptures and paintings.

Paintings which, as one critic spitefully wrote, are suited at best to being printed on spring dresses.

By Anna Batko

Maria Jarema, Designs of two costumes for K. Mikulski's "Circus", 1957, tempera and ink on paper, from the deposit of the National Museum in Wrocław, courtesy of Aleksander Filipowicz

Maria Jarema, Costume design for K. Mikulski's "Circus", 1957, tempera and ink on paper, from the deposit of the National Museum in Wrocław, courtesy of Aleksander Filipowicz

Maria Jarema (Maria Jaremianka): 1908–1958, Polish painter, sculptor, scenographer and actress. She studied sculpture at the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts in the studio of Xawery Dunikowski. She was a cofounder of the avant-garde Kraków Group and the 2nd Kraków Group. She cooperated with the experimental Cricot theatre, founded by her brother Józef Jarema, Adam Polewka’s puppet theatre, and the Cricot 2 theatre. In 1958 she represented Polish art at the 29th Venice Biennale.